An Early Lesson

The day after my college graduation, my roommates and I were packing up to leave. One roommate was preparing to drive halfway across the country to home and deciding what would fit in his car. He asked if I would make an offer for his loose change jar.

I had seen him depositing pocket change into the jar for the last 4 years each time he came home for the day. I had no idea how much money was in there, but offered $20, thinking that was a safe bet. He accepted. Two days later I took it to a Coinstar machine at my local supermarket, which converts your coins into bills for a 10% fee, and walked out with $180 in my pocket.

This was a powerful lesson in the value of taking the other side from a forced seller, even under conditions of uncertainty.

If such opportunities appeared on a regular basis, becoming wealthy could be “done before breakfast,” according to the Japanese saying. Sadly, that was the last time I was offered a dollar for 11 cents. But every so often the stock market presents such opportunities to those paying attention.

Poor Performance

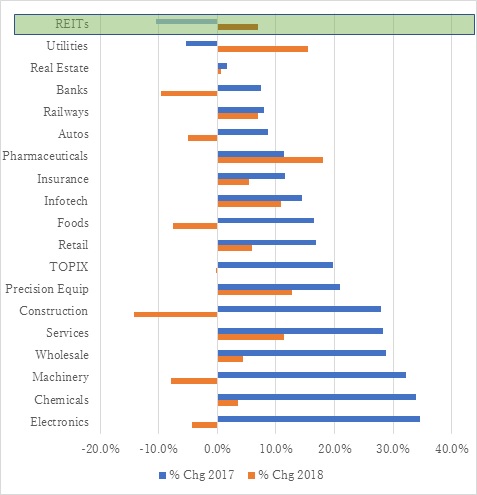

In late 2017 while the Nikkei 225 was in the middle of a 16-day advance streak, we were focused on researching J-REITs. J-REITs tend to be low-risk, low-return assets, while our preference at Varecs is for low-risk, high-return investments. However, at that time, nearly all stocks looked expensive to us, and REITs were having a terrible time. Despite ongoing strength in the Japanese real estate market including low vacancy rates and rising rents, REITs underperformed the Topix by 30%pt for the year (-10% vs. +20%). They also undperformed all 33 Topix sub-industries. The combination of falling market values and apparently rising intrinsic value was enough to spark our interest.

The chart below shows the performance of REITs against major TOPIX sectors in 2017 and for the first 9 months of 2018.

There appeared to be a forced selling wave in REITs, and we identified Nobuchika Mori, the head of the Financial Services Agency, as the root cause.

Mr. Mori was on a crusade against abuses in the financial industry, admonishing asset managers for not acting in the best interests of clients. Early in 2017, he criticized funds offering monthly dividend payouts because they provide the illusion of safety (a fixed monthly payout), when in fact the underlying can in truth be quite risky and the dividend unsustainable. This guidance resulted in brokers and asset managers ceasing marketing activities in these popular products, triggering a huge contraction in AUM for these funds due to redemptions and payouts.

One such example – there is a certain J-REIT fund that invests in assets yielding 4%, uses a currency hedge in a high yielding country (such as Turkey, Brazil or South Africa) to supercharge returns, and promises investors a 43% annual yield. How does the math work, you wonder? It doesn’t, of course. This is the logical consequence of setting a fixed dividend payout above the return the underlying can generate. The NAV shrinks over time as the fund is forced to sell assets to meet payouts. AUM declines spiral as the payout balloons relative to the NAV, likely leading to an eventual closure of the fund. The largest publicly offered J-REIT fund in Japan now offers a 10% annual yield and I calculate it will shut down in under 12 years if the REIT index stays flat. The octopus is eating its legs.

When the REIT market is rising and funds have inflows, this situation is not particularly consequential as monthly payouts can be met with inflows and a fund may actually increase its positions sizes if inflows are large enough.

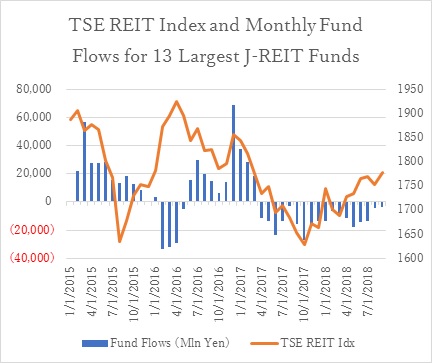

Once Mr. Mori, who should be regarded as a defender of individual investor, put a stop to the perpetual motion machine, the consequences were dire. Since April 2017, the 13 largest REIT funds have seen continuous outflows averaging nearly 13bn per month. Their continuous selling led to a sharp decline in J-REIT shares, which bottomed in November. This forced selling will likely continue until funds change their dividend policies, but the market impact is gradually lessening as AUMs have declined.

Selecting the Right REITs

When researching the market, we found it is full of little idiosyncrasies. J-REITs can be grouped into roughly three categories – Sponsor Controlled, Finance Oriented, and Investors. The Sponsor-Controlled REITs tend to be the largest, but their degree of independence is limited and principal-agent conflicts are rife. The Finance-Oriented REITs invest in decent properties, but differentiate by having strong ties to a major bank, lowering their debt costs substantially. The Investors are the ones that fit neither of these categories and are focused on maximizing returns to unit-holders by fixing up old buildings, sourcing properties that others miss, structuring unique deals and in general working a lot harder than their peers. We naturally gravitated toward this last group.

Bank of Japan

The Bank of Japan has its own distortive effect on the market with its asset purchase program. Unlike equities, where the BOJ is buying the broad Topix Index, for J-REITs the BOJ has special conditions. The REIT must trade at least 20bn yen per year and carry a rating of AA- or better. It is odd having a debt rating requirement for an equity investor, but the really odd thing is that regional banks appear to have adopted the same criteria for their investments. The net effect is a crowding of investors into J-REITs that match the BOJ criteria and a scramble by the J-REITs to match the requirements. The rating agencies don’t specifically disclose their criteria, but the consensus view is that a track record of a few years and 200bn in total assets are required to reach AA- or better. This has created a group of also rans – newer, smaller funds that may have perfectly attractive profiles, but that are largely ignored by the market for non-fundamental reasons.

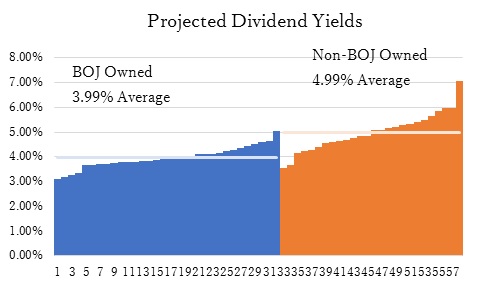

The below chart shows the dividend yield gap between J-REITs meeting the BOJ criteria and those that do not:

There is a full 1 percent point difference between the two groups, on average. We are partial to the higher yielding REITs both from a margin of safety perspective and for the 25% upside that would likely result from eventually being included in the BOJ buying club.

Chicken and Egg Problem

A number of REITs looked attractive based on trading at substantial discounts to their NAVs. These tended to be small REITs. Most large REITS trade at NAV premiums, helped by inclusion in global index funds and the BOJ program. REITs will generally not issue new shares at prices below 1x P/NAV (appraisal basis) because that would most likely destroy value for existing shareholders. Therefore, a low P/NAV REIT cannot grow, which means it can’t reach the size required to be included in indexes or get the credit rating required for the BOJ, which means its valuation will stay low. It is a funny chicken and egg type of situation.

However, starting in 2017, for the first time, a number of REITs conducted share buybacks using reserve funds. Buybacks had never been successfully done in the industry as the purchase pipeline creates a high insider information hurdle. A number of REITs also merged in order to achieve scale. These types of actions gave us more confidence in investing in low P/NAV REITs.

What Asset Type

The last consideration was what type of REIT to invest in. They broadly fall into Office, Retail, Logistics, Residential, Hotel, and Other. We don’t particularly enjoy macro forecasting, but it seemed evident enough that older, mid-sized office assets had a particularly attractive combination of characteristics. First, the stock is not growing, as the majority of new supply is on the high end. Second, rents are growing from tight supply demand. Third, most buildings in this category are 20-40 years old, so there is a lot of opportunity for a savvy owner to fix them up and undertake high ROI investments that will lead to rent increases. Such value-add activities are simply not possible for a top-grade Otemachi office building.

We also favor select logistics assets due to the bifurcation of the market between older warehouses and newer ones that are specifically tailored to the growing ecommerce market.

Considering declines were driven by forced selling, perhaps the most logical strategy would be to buy the REITs extensively held by mutual funds and experiencing the largest price declines. These tended to be large, stable, Sponsor Controlled funds. Unfortunately, we did not feel these REITs offered the right combination of downside protection, honest management and appreciation potential.

We limited our universe to Investor-oriented, non-BOJ owned, mid-size office or logistics REITs. We ended up purchasing nearly equal portions in 5 where we liked the management, the assets, and the strategy. Through September, our holdings returned an average of 10.7% (including dividends) compared with 9.7% for the TSE REIT Index and a 0% return for the Topix. Our REIT exposure has been working as ballast in our portfolio in highly volatile market environment. We don’t particularly love the asset class, and hope to eventually find more attractive opportunities in equities, but for now we are satisfied to be trading with forced sellers.